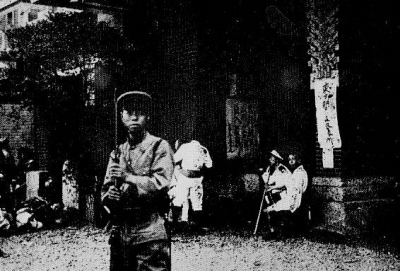

The sketch above is presumed to be painted by a well-known children's book illustrator Kawame Teiji. The date and location of the scene are uncertain, but it was probably by the Sumida River (See Arai Katsuhiro's article in The Great Kanto Earthquake in World History [Sekaishi to shite no kanto daishinsai), 2004). At the center of the painting is a member of a vigilante group (jikeidan) bringing his sword down on a collapsing man, probably Korean. There are bodies strewn at his feet as well. To the right are soldiers with bayonets pushing and herding someone else as well as policemen in their summer uniforms bringing another bound person with his hands behind his back to the massacre site. We do not know whether or not the artist drew this on the basis of direct observation, but we do know that he depicted a scene of massacre in which the military and the police worked together closely with the vigilantes. mer In Tokyo, ordinary people organized as vigilante groups or veterans' associations did the killing, but police and military also joined the massacre. Why did a massacre like this occur? In what ways were the government authorities and the people involved in this mayhem? And, how was the incident "settled?" As we think about these questions, we would like to bring to light the responsibilities of both the Japanese government and the people for the massacre of Koreans.

1. Why focus on the Massacre of The Koreans during the Great Kanto Earthquake Now?

Lingering "memory" of hte Great Kanto Earthquake

In the midst of the Great Kanto Earthquake, rumors broke out claiming that "Koreans put poison in wells," "set fires," and "instigated riots." As a result, many Koreans, Chinese, and Japanese became the victims of mass killing.

Some may think that this is just an event in the past. But the "memory" of the Great Kanto Earthquake is still evoked today. During the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of 1995, some people recalled what had happened during the Great Kanto Earthquake and were concerned about potential mistreatment of foreigners (See Otani Shigeaki's article in Ten Years Since the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake [Hanshin-Awaji junen], 2004). That anxiety was especially intense among the resident Koreans who feared becoming victims. This was never a baseless fear.

Five years later, on April 9, 2000, then Tokyo Governor Ishihara Shintarõ caused an uproar when he stated the following in a speech: "In Tokyo, atrocious crimes have been committed repeatedly by many illegal sangokujin ("Third Country Nationals," a derogatory term that refers to the former colonized people under Japan such as Koreans and Taiwanese) and foreigners. We can imagine that they might riot in the event of a big disaster." The image of "the rioting Koreans during the Great Kanto Earthquake was probably what he had in his mind. Such statements are prevalent in books and the internet. The idea that foreigners were dangerous travelled widely during the Great Kanto Earthquake. How did such an image of foreigners spread during the Earthquake in the first place?

Did the massaacre happen the post-quake "confusion"?

![Did the massacre happen during t Journalist Miyatake Gaikotsu's illustration of a rumor introducing the idea that a socialist couple and pregnant-looking Korean women were hiding pistols and bombs (Earthquake Pictorial [Shinsai gahō] vol. 1, September 25, 1923](/news/photo/202208/10584_10963_3815.jpg)

During the Great Kanto Earthquake laborers and students and the like from Korea and China were murdered by the Japanese people, the military, and the police. Also, political and labor activists, including Ösugi Sakae and Wang Xitien, were killed by the military.

Common narratives on the massacre, including textbooks, say that the rumors spread "in the post-quake confusion" and these incidents happened as a result. But nothing similar happened during the time of other earthquakes before or after the Great Kanto Earthquake. Therefore, we cannot say that the earthquake itself was the direct cause of the massacre.

Rather, government authorities were deeply involved in spreading the rumors and in the massacre itself. Under the martial law, the authorities spread the rumors as "facts," and the fact that the military took the lead in carrying out the massacres made the rumors even more credible.

Also, as shown in the timeline listed in the following section, the March First Independence Movement broke out in Korea four years prior to the Great Kanto Earthquake, and such movements continued to grow among Koreans. In this context, the image of Koreans as "rebellious" (futei) as they carried out independence movement intensified both in the minds of the Japanese people and the authorities. This is another factor behind the killing.

2.The Reality of the Korean Massacre

Why were Koreans in Japan at the time?

Students and other Koreans had travelled to Japan even before Japan's "annexation" of Korea in 1910. However, during the years around 1923, many more Koreans were making their way to Japan to work as laborers and merchants. Their actions were due to the fact that, as Japan was intensifying its industrialization, demand for labor in Japan increased even as living conditions in Korea under Japanese colonial rule deteriorated. Nevertheless, with the exception of students and live-in-workers, many Koreans who travelled to Japan neither spoke much Japanese nor had daily interactions with Japanese people. A great number of the massacre victims are believed to be these Koreans.

On the other hand, one will notice in some massacre survivors' stories that they were able to escape from being killed because individual Japanese who they knew protected them. One can say then that these daily interactions and mutual understanding between Koreans and Japanese turned out to be a matter of life and death.

Timeline of Modern Japan-Korea Relations

1876 Treaty of Amity (unequal treaty)

1894 Gabo Peasants Uprising (Donghak Movement)

The First Sino-Japanese War 1895 Assassination of Korean Empress Min

1904 Russo-Japanese War

1905 Protectorate Treaty & loss of Korea's sovereignty in foreign affairs.

Suppression of Korean resistance such as the Righteous Army

1910 Japan's forced "Annexation" of Korea Military rule.

1919 March First Movement & continuing Korean independence movement

1923 Great Kanto Earthquake & Korean Massacre

1925 Peace Preservation Law

1931 Manchurian Incident

1937 Second Sino-Japanese War. Kōminka policy

(Imperialization & Japanization)

1939 Wartime Mobilization of Korean Laborers (Forced labor conscription)

1941 Asia-Pacific War 1945 Japan's defeat. Liberation of Korea.

1945 Japan's defert. Liberation of Korea.

"They set the fires": Who spread this kind of rumors?

Rumors like "Koreans are setting fires" spread in Tokyo and Yokohama on the day of the earthquake. As the newspaper report at the right suggests, local police were responsible for their spread along with refugees fleeing the flames. In fact, the Ministry of Home Affairs (the government authority in charge of the police and local governments) played an active role in escalating these rumors. On September 2, the Ministry imposed martial law for the sake of maintaining public order, and, as records in Saitama Prefecture reveal, it issued a directive to each town via the prefectural office to be on guard and "take appropriate measures" against "rebellious Koreans" in cooperation with the local residents, since, the order stated, Koreans are carrying out "unruly behavior." In addition, the Ministry ordered the Naval Radio Transmitting Station at Funabashi to send a telegram throughout the country to tightly control Koreans since the martial law was imposed to prevent Koreans' "subversive" attempts (sent in the morning of September 3). It becomes clear then that the government was aggressively spreading the rumors.

Funabashi Naval Radio Transmitting Station's telegram to Governors

Telegram to Kure Naval District Aide-de-Camp

Sent at 8:15 a.m., September 3

From: Chief of the Home Ministry Police Bureau

To: All Governors

Taking advantage of the earthquake in the Tokyo area, Koreans are scheming to set fires and achieve their subversive goals in various areas. Currently, there are Koreans who possess bombs and are setting fires by pouring gasoline in the city of Tokyo. Since martial law has already been enforced in some parts of Tokyo Prefecture, observe and petrol your area meticulously, and take strict measures in response to the actions by Koreans.

The Home Ministry's Directive via Saitama Home Affairs Department Director

September 2, 1923

From: Director of Home Affairs Department in Saitama Prefecture

To: Village, Town, and County Governing Heads

Notification Concerning Rebellious Koreans Riots

In response to the earthquake disaster this time, rebellious Koreans in Tokyo are engaging in unruly behavior and also joining together with the radicals in pursuit of their goals....In light of these fearful circumstances, village and town officials are to cooperate closely with Veterans Associations, Fire Brigade units, and Young Men's Organizations to guard against such movements, and be prepared to take appropriate measures immediately in case of emergency. This is a notification to all local municipality officials upon receiving the directive from the authorities above.

How was the military involved in the massacre?

Military-led Massacre Examples

Based on Chapter 10 "On Military Behavior" in Investigative Report on the Post-Earthquake Crimes and Related Matters published by Ministry of Justice. Adapted from Kang Tok-sang and Kûm Pyongdong eds,. Gendaishi shiryō V. 6 Kanto daishinsai to Chösenjin. (Misuzu shobõ, 1963), 443-448.

![*As in the original source material.**The Report also records that there are another Korean who was mudersd by the local residents.Notes: Also included in the Report are: Sep. 4, near Minamigyōtokumura Hongyōtoku,3 Koreans by shooting, which was determined to be groundless after investigation; Sep.3, charge ofinstigation to murder Koreans for Lietenant Omori Ryozo, the officer in charge of the Naval Radio Transmitting Station at Funabashi, which was excluded from investigation due to its irrelevance to the Army; Sep. 4, Minamigyōtokumura, murder of3 Koreans, the case in which solders failed to stop the local residents from killing Koreans; Murder of 1 Korean in Ichikawamachi where "the convoys showed no concern [about the killing]."](/news/photo/202208/10584_10966_256.jpg)

*As in the original source material.

**The Report also records that there are another Korean who was mudersd by the local residents.Notes: Also included in the Report are: Sep. 4, near Minamigyōtokumura Hongyōtoku,3 Koreans by shooting, which was determined to be groundless after investigation; Sep.3, charge ofinstigation to murder Koreans for Lietenant Omori Ryozo, the officer in charge of the Naval Radio Transmitting Station at Funabashi, which was excluded from investigation due to its irrelevance to the Army; Sep. 4, Minamigyōtokumura, murder of3 Koreans, the case in which solders failed to stop the local residents from killing Koreans; Murder of 1 Korean in Ichikawamachi where "the convoys showed no concern [about the killing]."

Notes: Abbreviations for perpetrators indicate as following: IR (Infantry Regiment), CR (Cavalry Regiment), IGR (Imperial Guard Regiment), FAR (Field Artillary Regiment), AES (Army Engineering School), NCO (Non-commissioned Officers), TC (Telegraph Corps).

* Regarding the military's role, the Report reads: "The military tried to prevent a fight that Koreans caused against the mob and police officers."

** The Report says the military killed 17, and the rest of Korean victims were killed by "the refugees and police officers."

*** Kawai Yoshitora and others. As in the original source material.

The two tables above are based on the investigative reports by the government and the military documenting the military's involvement in the massacre at that time. The case of Ojiimamachi in which Chinese laborers (and perhaps some Koreans) were murdered is recorded here. There are eyewitness accounts testifying to other military-led massacre cases in various sites such as the Arakawa River bank, so it is likely that these reports understate what actually happened.

The writer Etchüya Riichi, who was a soldier in the Narashino Cavalry Regiment, was dispatched to Kameido with live ammunition as if going to war, and witnessed the following scene: "The Officer, sword in hand, searched the interior and exterior of the train cars....All the Koreans were dragged out, and fell immediately under swords and bayonets one after the other. Among the Japanese refugees arose like a storm the exuberant cries of "Banzai": "Traitors! Kill all the Koreans!" (From Etchüya Riichi, "Kanto daishinsai no omoide, Etchũya Riichi chosakushũ, 1971).

The facts in the tables above were never released by the Japanese funeral government. The authorities neither admitted their crimes nor apologized to the victims' families, but instead have hidden their direct and indirect involvement in the massacre at all costs.

What happened in each site?

In Tokyo and the Arakawa riverbed area

The following is a testimony concerning what happened in the Sumida Ward of Tokyo: "The Koreans were brought to the southern embankment at Arakawa Station (now Yahiro Station), and as they were lined up there facing the river, the soldiers shot them with machine guns. Once shot, they fell and rolled down the bank. But some didn't roll down. How many had been killed? It was quite a lot. I was made to dig a hole. Afterwards, the dead bodies were burnt with gasoline and buried." This happened by the old Yotsugi Bridge. Other testimonies said that there were massacres by civilians beginning on the night of September 1st in this area.

The Massacre and the Burial of the Remains in Yokohama

There are almost no available records of the Korean massacres in Yokohama, but we do have testimonies such as the following elementary school student's words: "Once I got close to Nakamura Bridge, I saw a lot of people there. So I went ahead and saw a Korean who was beaten. Then he was thrown into the river. The Japanese along the river continued to follow him, and then eventually jumped in from either side of the bank, one by one, and hit him in the head with a fire hook. He died in the end" (Minamiyoshida Second Elementary School student's essay). Later, a man named Yi Seongchil collected the remains and tried hard to arrange a memorial service at a temple. Eventually Muroji accepted his request. The services for the victims still continue today.

![Newspaper reports of the order from the Ministry of Affairs, [Tokyo nichinichi shibun], NOV.2 and Oct. 22, 1923.](/news/photo/202208/10584_10974_440.jpg)

In Saitama and Gunma newspaper reports of rumors and the Home Affairs Ministry's order were in the background of the massacre.

In Saitama and Gunma, many towns and villages organized self- defence units once the Home Ministry's orders and rumorsespecially through newspaper reportsbegan to reach them. Vigilantes attacked Kor eans in places such as a police station where Koreans had been taken into custody as well as on the road along the Nakasendo line while the police were transporting Koreans to Gunma. Confirmed incidents include those at Õmiya, Yorii, Kodama, Kumagaya, Honjõ, Jinbohara in Saitama Prefecture, and Fujioka and Kuragano, etc. in Gunma Prefecture. Research has shown that the number of Korean victims was about 200 in Saitama and 20 in Gunma.

Cases in Chiba Prefecture in which local residents were made to participate in the killings

In Chiba Prefecture, the Funabashi Naval Radio Transmitting Station became a source for rumors, and the director of the Station distributed weapons to local residents ordering them to be on guard against Koreans. In Funabashi, Korean railroad construction laborers were dragged out and given to vigilantes to be massacred. In addition, there were also incidents elsewhere in Chiba at Urayasu, Minamigyōtoku, Mabashi and Abiko among others. Cases involving the vigilante bands came to an end by September 6 following the Martial Law Headquarters' issue of a "Warning" against vigilante violence. However, at the internment camp at Narashino where Koreans and Chinese were being held, the military police separated Koreans into groups to kill those who "had wrong thoughts" and sent them to local villagers to be killed. We know about this based on the evidence of testimonies, village residents' diaries, and the remains of the victims excavated in 1998 among others.

Yagigaya Taeko's testimony concerning the case in Chiba With the tied up person (the Korean who had been handed over to the villagers) at the front, they walked the dusty road to the cemetery for about ten minutes. The cemetery already had a hole dug. · ..The person who had been dragged was blindfolded and then tied to a pine tree. .He was shot, and then buried in the hole. By then, I got so terrified that I fled the scene and ran back home.

3. Concealed Facts of the Massacres

Has the Japanese government taken responsibility for the spread of rumors and the massacre?

Fabricated "subversive" acts by Koreans

The military and police never discovered any group of Koreans engaged in "subversion." On the other hand, persecution of Koreans continued to proliterate. The Japanese government, after sowing the seeds of the massacre, later realized that it had to end the killing. On September 4 the Security Division of the Emergency Earthquake Relief Bureau prohibited vigilantes trom carrying weapons or setting up checkpoints. On the following day the Cabinet issued its official notice (No. 2) forbidding taking actions against Koreans and reporting of the rumors in newspapers.

On the very same day, government security authorities assembled and made arrangements as to what position the government should take toward outside criticism concerning the massacre: to certify the rumors as fact. The reason was that if the government's information was found to be wrong, the authorities would not be able to avoid the responsibility for the Korean massacre both inside and outside of Japan. Hence, the state involvement in the Korean massacre was concealed.

On October 20, the Ministry of Justice released a statement on the "crimes" committed by Koreans to coincide with the lifting of the ban on reporting the vigilante violence against Koreans. Yet, almost none of those crimes allegedly committed by Koreans included the names of the perpetrators, thus it was impossible to tell whether they were actually Koreans, nor indicated that there was any aforementioned "organized" crime.

The remains taken away

On the left is a newspaper article showing police officers refusing to allow the family members of the victims in Kameido to approach one of the sites where the massacred bodies were buried. The authorities, in fear of revealing evidence of the mass killings, tried to dig up all the remains of the victims there, whether they were Japanese or Koreans, before their families could claim them. There is no record of the Japanese government ever delivering remains to the families of the Korean victims, or offering apologies or compensation. There is even a document produced by the Government-General of Korea which stated "Dispose the remains in a way that they cannot be identified as Japanese or Korean.

Answer during Diet questioning: "Currently under investigation"

On December 14, 1923, Diet member Tabuchi Toyokichi (Independent) pursued the government's responsibility for the Korean massacres during Japan's Imperial Diet session as follows:

I feel great indignation and sadness that all the members of the cabinet have not a word to report to this sacred Diet regarding the significant incident that was the most tragic from the standpoint of humanity. Is it acceptable to keep silence about such a big incident involving the murder of over a thousand people? Is it the idea that it is okay because the victims were Korean? We think that it must be taken as a human courtesy that we apologize when we have done something wrong.

The following day, Nagai Ryutaro of the Kenseikai party also persisted in asking questions about government responsibility in this matter. In response, Prime Minister Yamamoto Gonnohyōe answered that "The government is currently investigating what occurred," but the Japanese government has never followed up until this day.

Were the people asked to take responsibility?

On September 11, 1923, the Security Division's Justice Committee under the Emergency Earthquake Relief Bureau of the government decided to adopt the following policies: It will arrest only some participants in the massacre of Koreans, but will take strict measures to apprehend those who were rebellious against the police. Arrests of civilians on murder charges began from September 17, but under the aforementioned policies, arrests and trials were concluded in an extremely inconsistent and incomplete manner. Furthermore, the massacres committed by the military were not pursued. During the trials, some defendants claimed that they had killed Koreans "for the sake of the state." Their defense reveals the way in which they were thinking about the situation as if they were in a state of war: With the government endorsement, they killed those "terrifying Koreans who were scheming independence conspiracies."

The rulings and sentences for the charge of killing Koreans were lighter than cases in which Japanese were murdered or police stations were attacked But even so, the defendants criticized the government for placing the blame on the vigilantes alone, and demanded that sentences be reduced. In this way, arrests and trials were conducted while taking into account the people's complaints. This meant the human rights of the Korean victims were ignored, and even the trials revealed pervasive racial discrimination.

Are the victims known?

After the earthquake, a group of Korean young men conducted an investigation of the massacre in the name of paying a condolence visit to the Korean disaster refugees. They concluded that there were over six thousand massacre victims, although they could not establish the precise number of victims. Recent studies have also suggested that it will be impossible to spec ify the exact number of victims (Yamada Shoji, Kanto daishinsai ji no Chosenjin gyakusatsu, 2003).

The reason is that such investigations of the matter were stymied and the remains were hidden, meaning that we need to think about why even the number of victims remains obscure.

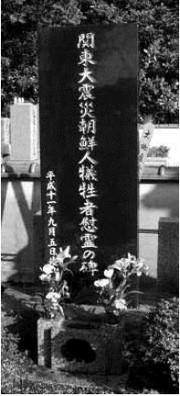

There have been graves and memorials built to the Korean victims in various locales, but only a few of them can be identified by name, and their bereaved families are also unknown. There are people who do not know what became of their family members.

Leaving Behind Three Small Children and a Wife (Kim Doim, Tokyo resident)

The Great Kanto Earthquake occurred 13 years before I was born. It was at this time that my mother's older brother, Bak Deoksu, became a victim. My uncle was working in Gunma, but set off for Tokyo following the earthquake. The folks from the same hometown as his tried to stop him from going, warning him of the danger. But my 33-year old uncle departed anyway, saying "I know the Japanese language as well as the area. Since then we have not heard from him. In his hometown, he left behind a young daughter and two small sons as well as a 28-year old wife. My uncle was 10 years older than my mother, and always took great care of my mother who married at the age of 16. My mother greatly respected her brother Deoksu as well. My mother fell ill from shock at what happened to him, and apparently it even caused her breast milk to stop. Thinking that he was killed simply because he was Korean, how upsetting and regrettable it must have been. Even I have been plagued by nightmares around September every year. My cousins, left as orphans, have erected a cenotaph at an empty tomb with no remains buried for my uncle Bak Deoksu next to their mother's grave in their hometown. My grandchildren, the fourth generation Korean residents, also live in Japan. I cannot stop hoping that Japan will head toward the right direction, so that such a fearful thing will never happen again.

4. Remaining task : What Needs to Be Done Now ?

Ms. Mun Museon's Human Rights Relief Request to the Japan Federation of Bar Associations (JFBA, filed on December 10, 1999) 1) Recognize that the massacre of Koreans during the Great Kanto Earthquake was "genocide," and is a serious violation of human rights. 2) Clarify that, since the Korean massacre involved mass killing of foreigners, there remains the responsibility for the crime of genocide against foreign nationals according to international laws. 3) Clarify the responsibility of the Japanese government for failing to prosecute the perpetrators of the genocide by the Japanese laws. 4) Demand that the Japanese government admit and apologize for its responsibility for the massacre, and take appropriate measures to prevent another genocide against foreign residents and Korean residents in Japan. JFBA conducted an investigation based on the request above, and delivered the following recommendation to the authorities (August 25, 2003) 1) The government shall acknowledge its responsibility and apologize to the victims and their families for the following massacres involving Koreans and Chinese during the Great Kanto Earthquake: The military-led massacre and the vigilante massacre which was induced by the government's spread of false information. 2) The government shall investigate the whole facts regarding the massacre of Koreans and Chinese, and clarify the cause.

Mun Museon, who filed the human rights relief complaint above, has a deeply paintul experience after witnessing the dead bodies of fellow Koreans. Her father's acquaintance was among the murdered. Upon receiving her request, JFBA carried out an investigation, and delivered its recommendation to the Japanese government in 2003. However, then Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro ignored it.

In the postwar era, resident Koreans and Japanese have carried out memorial services for massacre victims in various parts of Japan, and these gatherings still continue to this day. New evidence has been discovered, and more testimonies have been collected. Despite such arduous efforts by concerned citizens, however, even the names of the majority of the victims still remain unknown.

Why do we know so little about the victims? Because it was the Japanese government itself that spread the rumors and murdered Koreans, the authorities concealed the facts in fear of having to take the responsibility. Citizens have been complicit in this cover-up process. Even now some deny the massacre claiming that "the Korean massacre is a phantom" or "the massacre was self-defense against Korean riots that did exist." However, it is clear that these claims cannot be sustained.

Today, the Kanto massacre of Koreans still remains unsettled. Moreover, the background factors behind this massacre, such as discrimination, hatred, exclusivity and persecution against foreigners, still continue in Japan. This will continue until the government admits its responsibility, apologizes to the bereaved families, and moves forward with its efforts toward a true settlement of the case. Activism to demand the government make such efforts would bring us a step forward toward creation ofa society that would leave no room for xenophobia.

Copyright@2013 by the Committee on State Responsibility for the Kanto Massacre of Koreans. Translated by Jinhee Lee with contributions by Alex Bates, Andre Haag, and Kerry Smith. All rights reserved.